Chapter One

“I don’t get it, Mom. If this is our house, why are other

people going to live here?” My daughter Melissa, nine years

old and already a prosecuting attorney, looked up from the

baseboard near the window seat in the living room, which she

was painting with a two-inch brush and a gallon can of

generic semi-gloss white paint. Never use the expensive

stuff when you’re letting a fourth grader help with the

painting.

“I’ve explained this to you before, Liss,” I told her

without looking down from the wall. I was trying to locate a

wooden stud, and the stud finder I was using was being, as

is often the case with plaster walls, inconclusive. Using a

battery-operated gizmo to find a stud and failing: I tried

not to dwell on its metaphorical implications for my love life.

“Other people aren’t coming here to live,” I continued.

“They’ll be coming here when they’re on vacation. We’re

going to have a guest house, like a hotel. They’ll pay us to

stay here near the beach. But we’ve got to fix the place up

first.”

“Mr. Barnes says these houses have history in them, and it’s

wrong to make them modern.” Mr. Barnes was Melissa’s history

teacher, and at the moment, he wasn’t helping.

“Mr. Barnes probably didn’t mean this house. Besides, we’re

fixing it up the way it is meant to be. I mean, no one would

want to live in the house the way it looks now, right?”

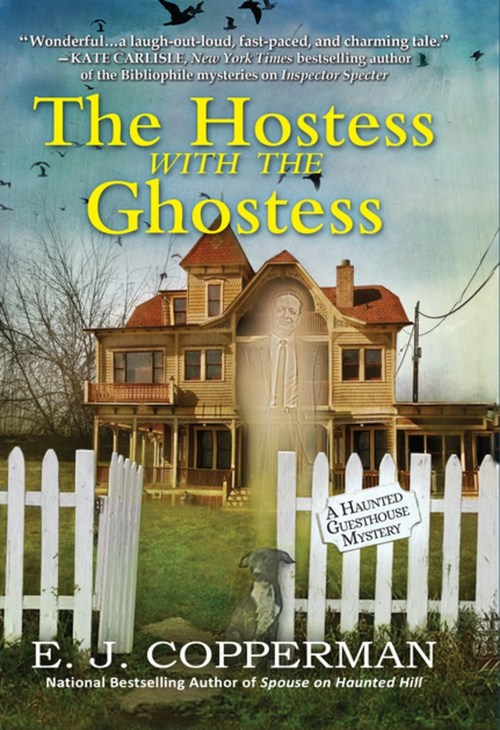

Our hulk of a turn of the last century Victorian house was

not, by the standards of anyone whose age was in the double

digits, livable. Sure, the house had once been adorable,

maybe even grand, but that was a long time ago.

Now, the ancient plaster walls downstairs were peeling, and

in some places, crumbling. There was a thick coat of white

dust pretty much everywhere, and as far as I could tell, the

heating system was devoid of, well, heat. The October chill

was already starting to feel permanent in my bones.

However, it was clear some work had been done by

the previous owner, though by my decorating standards, he or

she must have been demented. The living room walls had been

painted bright, blood red, and the kitchen cabinets were

hideous, and hung so high Shaquille O’Neal would have a hard

time reaching the cereal. Luckily, the upstairs walls had

been patched and painted, the landscaping in the front of

the house was quite lovely (although the vast backyard had

been untouched), and the staircases (there were two) going

upstairs had been refinished beautifully. It was a work in

progress. Slow progress.

“I would live here,” Melissa said, and went back to

painting. That settled it, in her view.

“You do live here,” I answered, not noting that

there was no furniture, and we were both sleeping on

mattresses laid directly onto the floors of our respective

so-called bedrooms and living out of suitcases. Why remind

her of all the things we’d left in the house in Red Bank

after the divorce? Melissa’s father Steven (hereafter known

as The Swine) hadn’t wanted the furniture, but he

did want half the proceeds when I sold it all to

help make the down payment on the house. The Swine.

Besides, now the house was a construction site, and any

furniture would be prone to disfigurement or worse while the

work went on. As soon as the house was in shape, the new

furniture I’d ordered (and in some cases, collected from

consignment stores) would be delivered.

I hadn’t put down a drop cloth where Melissa was working,

because I was going to paint the rest of the wall after I’d

made my repairs, and the wall-to-wall carpet in the living

room was among the first things I’d decided to remove when I

first saw the house. Giving Melissa woodwork to paint was

going to be little help in the long term, but mostly, it was

a good way to keep her busy.